What’s New?

Terror attacks on schools, especially in northern Nigeria, are responsible for the killing and abduction of thousands of students and teachers. Analysis of data collected by the Nigeria Security Tracker (NST) shows that between 2012 and 2022, there were at least 359 violent attacks on schools in the country, leading to the death of 1,985 people and the kidnapping of 1,725 others. The most gruesome of these attacks were those orchestrated by terror groups in the northeastern and northwestern regions of Nigeria.

These schools have become an easy target because they and their host communities lack adequate security infrastructure. The students are at risk of sexual violence or becoming forcefully conscripted by armed groups. Schools may also be shut down or commandeered as camps for displaced people.

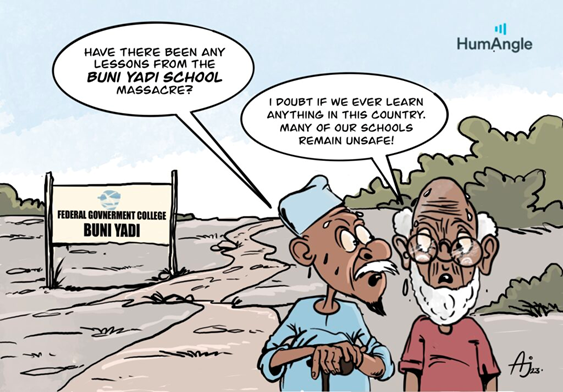

Between 2022 and early this year, HumAngle published over a dozen reports about major attacks on schools in Borno, Yobe, and Kebbi states – including the 2014 attack on the Federal Government College, Buni Yadi; the abduction of girls from the Government Girls Secondary School Chibok in the same year; the abduction of girls from the Government Girls’ Science and Technical College Dapchi, in 2018; and finally the abduction of schoolchildren from the Federal Government College Birnin Yauri, in 2021. Many of these articles examined the fallouts of these attacks.

Key Findings

- Students from the schools in Dapchi and various parts of Borno were moved to Nguru, Maiduguri, and safer areas following the attacks. This has led residents to lose confidence in the government’s ability to protect them and ultimately led to lower school enrolment rates and a growing disinterest in formal education.

- Some students did not return to school because of threats from their abductors. Others did, but were too afraid to advance their studies and pursue degrees from a tertiary institution.

- After the attacks, especially in Dapchi and Chibok, many students dropped out. Some transferred to Qur’anic schools and some girls simply got married and left education.

- Students moved to new schools and those enrolled in higher education, like the Chibok girls, have faced discrimination and social exclusion in their new environments.

- Students in new school environments also complain of not being able to afford textbooks, personal computers, student association levies, and other essential school needs.

- The students and teachers had been ill-prepared for such incidents despite the frequency of attacks in the region, with the schoolchildren not knowing what signs to look out for to distinguish terrorists from soldiers and the school not having adequate emergency protocols.

- The security agents responded poorly and slowly, especially in situations where the invaders had been sighted and it had been suspected that they were heading for the schools, or where they had written a warning they were coming prior to the attack. In the case of the kidnapping in Birnin Yauri, four police officers were present at the school entrance when the attack took place (as opposed to the 12 assigned to guard the premises), and they were easily overpowered.

- Many of the victims did not receive support from the government following the attacks – neither financial compensation nor condolence visits. There has also not been psychosocial support for the parents, many of whom have to bear the death or continued abduction of their children.

- During cases of prolonged abduction, the parents and loved ones of the victims often feel neglected by the government. They are not updated about efforts to rescue the captives, nor do they have reliable means of sharing their concerns. Where it has made provisions in the budget for victims of school attacks, such as in the case of the Chibok girls, the government has not been clear about how the funds are spent.

Why Does it Matter?

Nigeria has the highest number of out-of-school children in the world, about 20 million, despite laws providing for free and compulsory basic education.

Insecurity, especially in the form of attacks on schools, affects the education of the students and keeps children and teachers at home. Even when it seems like the attacks are over, parents are hesitant to allow their children to return to school. This increases the number of out-of-school children, decreases literacy levels, worsens poverty indices, and leads to a rise in crime, gender-based violence, drug abuse, and other vices. On a larger scale, this trend negatively impacts the quality of human capital in the country.

In a region where we are trying to counter violent extremism by encouraging literacy, a generation of out-of-school children will be easy fodder for the extremists to radicalise, manipulate, and exploit in their violent campaigns.

What Should Be Done?

To address the impact of the Boko Haram insurgency and other violent crises on education, the government should:

- Design and implement programmes tailored to the needs of the victims, such as sponsoring their education or providing vocational skills and business grants. Provide moral and psychological support for victims of school attacks through visits from high-level state officials and reassurances of safety. Victims should also be able to access therapy and counselling.

- Step up efforts to improve security in affected communities and revive abandoned schools to wrestle control from the armed non-state actors and provide freedom for academic activities.

- Provide alternative learning modes for people in remote communities, unsafe places, and displacement camps.

- Improve the infrastructure of schools that were attacked, those hosting students from attacked schools, and schools generally located in areas battling insecurity. The schools should also be adequately staffed and equipped. Provide more funding for psychosocial support for victims of attacks and be more transparent with how such money is expended.

- Inform parents whose children have died in captivity, especially in the case of the Chibok abduction, of the fate of their children so that they can begin the process of healing.

Civil society and media organisations should:

- Revisit old cases of school attacks and get updates about the welfare of the victims and the state of the affected schools, and not only focus on trending issues.

- Mount pressure on the government to improve the security of schools and provide for the needs of the victims of school attacks.

- Support victims through psychosocial interventions and scholarship opportunities.

- Sensitise communities across the country, especially in conflict areas with low school enrolment rates, about the need to educate children while also providing support to make this easier for parents and their children.

Conclusion

As the government seeks to consolidate its efforts in countering violent extremism, reducing crime, and tackling the problem of out-of-school children, it must also ramp up efforts to ensure uninterrupted education for children in conflict areas.

Additional Reading

- Keeping Up With The Chibok Girls: Chasing Dreams, Battling Discrimination, Dropping Out

- The Dapchi Girls’ Dashed Hopes Of Education, Empowerment

- #DapchiAbduction: Many Of The Girls Got Married After Their Release. Why?

- #DapchiAbduction: Before Her Abduction, Fatima Hoped To Become A Nurse

- #DapchiAbduction: Because They Went To School, They Paid With Their Lives

- The Buni Yadi Tragedy: When The Boys Came

- The Buni Yadi Tragedy: The Boy Who Saw It Coming

- The Buni Yadi Tragedy: Through The Grief Of A Father

- The Schoolgirls Of Birnin-Yauri: Living Through The Pains Of Captivity

- A Parent’s Worst Nightmare

- A Narrow Escape from Dogo Gide’s Camp